Jan 7, 2017 - Explore Daisy Concha's board 'Visayan Tattoo' on Pinterest. See more ideas about filipino tattoos, filipino culture, filipino. Tattoo Designs Ideas for Men and Women. A traditional tattoo artist and researcher. 'Visayan Tattooing and Tattoo Designs'. Visayans (Visayan: Mga Bisaya, local pronunciation: ) or Visayan people, are a Philippine ethnolinguistic group native to the whole Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and many parts of Mindanao.They are the largest ethnic group in the geographical division of the country when taken as a single group, numbering some 33.5 million. The Visayas broadly share a maritime culture with strong. Tattoo Process As proud indigenous Filipinos we are doing our little bit to revive a vanished tradition of our native home land and we encourage other Filipinos to do the same. It is important that we seek as much knowledge from our parents, grandparents and elders, share stories and learn from them before it's too late.

TATTOO PRACTITIONERS IN THE VISAYAS

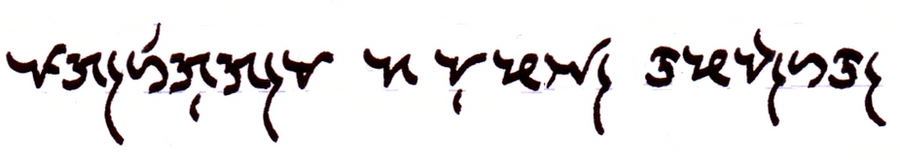

Patik is the most familiar preconquest Filipino word for 'tattoo'. It is a Visayan term that means 'to strike, mark, or print'. And it was the 16th-century Spaniards who named the Visayans — or more correctly, the Bisaya or Bisayans — as the Pintados, which means 'the painted ones'.

THE ISLAS DE LOS PINTADOS

The Spaniards were also the ones who christened the Visayan Archipelago or the Kabisayaan as the Islas de los Pintados, which is now the modern-day Bohol, Cebu, Leyte, Masbate, Negros, Panay, and Samar Islands. Hence, this resulted in the popularization of the precolonial Philippine tattoos with the Bisayans and the Visayan Archipelago.

A WIDESPREAD PRACTICE

However, despite the saturation of Bisaya tattoos in historical literature, the culture of the precolonial Philippine tattooing was not confined in the Visayan Archipelago alone — the peoples of Luzon and Mindanao had also practiced this ancient art.

TATTOO PRACTITIONERS IN LUZON

AGTAS

Among the tattoo practitioners of Luzon were the Agtas, and they called their tattoo as pika. As for the coastal Agtas or the Dumagats, they named their tattoo as cadlet.

Download microsoft lync instant messaging. Download Lync 2013 for Windows for free, without any viruses, from Uptodown. Try the latest version of Lync 2012 for Windows. Windows / Internet / Instant Messaging / Clients / Lync / Download. Instant messenger in your Office.

Traditional Visayan Tattoo Design

BIKOLANOS

The Bikolanos of Albay, Camarines, and Catanduanes were tattooed, and they also practiced head binding and observed the dental arts of teeth sharpening, staining, and gold pegging — which were similar to the customs of their Bisayan neighbors.

IBANAGS

The Ibanags of Cagayan Valley called their tattoo as appaku, which is derived from the word paku that means 'fern' due to its fern-like tattoo motifs.

IGOROTS

The Igorot people, specifically the Kalingas and the Ifugaos, called their tattoo as batok and their tattooist as mambabatok. The Igorot tattoo may also be called as whatok by the Butbuts, fatek by the Bontocs, bátak by the Kankanaeys, and bátek by the Ibaloys and the Sagadans.

ILOKANOS

The Ilokanos had tattoos called bátek, but their tattoos were not as extensive as the patiks of the Bisayans as observed by the 16th-century chronicler Father Pedro Chirino.

TATTOO PRACTITIONERS IN MINDANAO

KARAGANS

In 1521, Butuan and Caraga were mentioned by Pigafetta, and he described that one of its rulers was good looking, perfumed with storax and benzoin, and had three gold spots on every tooth — and was richly tattooed.

DAPITANONS

In 1563, the tattooed Bisayan families of Bohol, led by Datu Pagbuaya, migrated and established a Malayan kingdom in Dapitan; thus, they became the ancestors of the tattooed Dapitanons.

KAGAYANONS

In 1622, the Recollect priests visited Cagayan de Oro and met with the tattooed Kagayanons, who traced lineage from Bukidnon and Bisaya marriages.

MANOBOS

The Manobos called their tattoo as pangotoeb, their tattooist as mangotoeb, and their tattoo practice as pagpapangotoeb.

BAGOBOS

And according to a 20th-century account, some Bagobos had their tattoos done by their Manobo neighbors.

TATTOO DESIGNS

Visayan Tribal Tattoo Designs And Meanings

The precolonial Philippine tattoo designs were mostly abstract and geometric forms. And it is believed that these tattoos were more than ornamental — they were sacred and held meaning and purpose to each regional tattoo practitioner across the islands.

SACRED ANIMAL MOTIFS

Powerful or auspicious animals, such as pythons, crocodiles, eagles, birds, dogs, centipedes, scorpions, crabs, lizards, and other creatures, were depicted in traditional tattoo motifs.

SACRED NATURE MOTIFS

There were also nature tattoo designs, such as sun, moon, rain, mountains, fire, and lightning; and there were flowery patterns, such as lilies, lotuses, ferns, hibiscus, fruits, and various medicinal plants. 7: on thin ice.

OTHER SACRED MOTIFS

Everyday item motifs, such as compasses, ladders, poles, and arrowheads, were used. And other motifs, such as various geometric shapes, teeth, human figures, and names, were made into tattoo patterns.

TATTOO MATERIALS

Generally, a sharp object and a soot mixture were the tattoo materials in the precolonial times. The soot, which served as the pigment, might come from the burnt ashes of bamboo, dongon-dongong, sai-yung, salumayag, or almasiga plants.

This soot was often mixed with little water or some sort of liquid, like hog bile for the Ibanags, and the Spaniards suspected that this soot was mixed with blood. This precolonial soot mixture, which served as the tattoo ink, is called biro by the Bisayans.

As for the sharp object, it was usually a knife, lemon thorns, or other needle-like tools — a hammering stick would be an additional implement if the sharp object was not a metal blade.

TATTOO PROCEDURE

In the olden times, the tattooist would draw the sacred pattern on the recipient's skin with their soot mixture. Next, the tattooist would poke, prick, incise, or puncture the skin, following the tattoo design. Then, the tattooist would rub the fresh wounds with their soot mixture to make it more visible and permanent.

TATTOOIST PROFILE

Recent studies reveal that the profession of the preconquest tattooing was not exclusive to one gender. The Manobo tattooists were mostly females, and some were effeminate males who vowed to sexual purity, and they were traditionally paid for their services with beads, leglets, and food.

Visayan Tattoo Design And Symbol Images

It is also believed that tattooing was a lucrative profession and highly respected in the olden days. Some renowned tattoo artists would travel to different villages and tribes, for they were highly sought after for their services.

Historical narratives often compared and connected the precolonial tattooing with the traditional embroidery and weaving; hence, the tattoo artists were most likely learned weavers.

Lastly, considering the sacredness of the preconquest tattoos, it may be assumed that the tattoo artists were heavily connected with the area of ancient spirituality and practices, such as Binabaylan, Diwatahan, or Paganitohan.

REASONS FOR TATTOOS

Conventional wisdom dictates that the preconquest Philippine tattoos were only reserved for the warrior class; however, this popular statement proves to be inaccurate, for a non-warrior male, a female, and even a child, might be permitted or encouraged to have a tattoo. There were varied reasons on why to have a precolonial tattoo:

FOR IDENTIFICATION

In the olden times, tattoos were used to identify a person's tribe and address, and it could even reveal the person's name, profession, and social stratification.

FOR COMING-OF-AGE NOTICES

The Manobos started tattooing their children upon the start of their puberty. As for the Bisayans, they have a term called tigma that means a youth's first taste of sex, while tiklad is their first victory in love — and they were tattooed for these life events and for laudatory notices.

FOR THE VICTORIOUS WARRIORS

Animist champions or war leaders, such as the baganis, maganis, mangubats, or datus, were tattooed to commemorate and celebrate their feats. These warrior-type tattoos were likened to medals of honor. Thus, a man whose body was covered with warrior-type tattoos was perceived to be a very powerful and capable warrior.

Traditional Visayan Tattoo Design

BIKOLANOS

The Bikolanos of Albay, Camarines, and Catanduanes were tattooed, and they also practiced head binding and observed the dental arts of teeth sharpening, staining, and gold pegging — which were similar to the customs of their Bisayan neighbors.

IBANAGS

The Ibanags of Cagayan Valley called their tattoo as appaku, which is derived from the word paku that means 'fern' due to its fern-like tattoo motifs.

IGOROTS

The Igorot people, specifically the Kalingas and the Ifugaos, called their tattoo as batok and their tattooist as mambabatok. The Igorot tattoo may also be called as whatok by the Butbuts, fatek by the Bontocs, bátak by the Kankanaeys, and bátek by the Ibaloys and the Sagadans.

ILOKANOS

The Ilokanos had tattoos called bátek, but their tattoos were not as extensive as the patiks of the Bisayans as observed by the 16th-century chronicler Father Pedro Chirino.

TATTOO PRACTITIONERS IN MINDANAO

KARAGANS

In 1521, Butuan and Caraga were mentioned by Pigafetta, and he described that one of its rulers was good looking, perfumed with storax and benzoin, and had three gold spots on every tooth — and was richly tattooed.

DAPITANONS

In 1563, the tattooed Bisayan families of Bohol, led by Datu Pagbuaya, migrated and established a Malayan kingdom in Dapitan; thus, they became the ancestors of the tattooed Dapitanons.

KAGAYANONS

In 1622, the Recollect priests visited Cagayan de Oro and met with the tattooed Kagayanons, who traced lineage from Bukidnon and Bisaya marriages.

MANOBOS

The Manobos called their tattoo as pangotoeb, their tattooist as mangotoeb, and their tattoo practice as pagpapangotoeb.

BAGOBOS

And according to a 20th-century account, some Bagobos had their tattoos done by their Manobo neighbors.

TATTOO DESIGNS

Visayan Tribal Tattoo Designs And Meanings

The precolonial Philippine tattoo designs were mostly abstract and geometric forms. And it is believed that these tattoos were more than ornamental — they were sacred and held meaning and purpose to each regional tattoo practitioner across the islands.

SACRED ANIMAL MOTIFS

Powerful or auspicious animals, such as pythons, crocodiles, eagles, birds, dogs, centipedes, scorpions, crabs, lizards, and other creatures, were depicted in traditional tattoo motifs.

SACRED NATURE MOTIFS

There were also nature tattoo designs, such as sun, moon, rain, mountains, fire, and lightning; and there were flowery patterns, such as lilies, lotuses, ferns, hibiscus, fruits, and various medicinal plants. 7: on thin ice.

OTHER SACRED MOTIFS

Everyday item motifs, such as compasses, ladders, poles, and arrowheads, were used. And other motifs, such as various geometric shapes, teeth, human figures, and names, were made into tattoo patterns.

TATTOO MATERIALS

Generally, a sharp object and a soot mixture were the tattoo materials in the precolonial times. The soot, which served as the pigment, might come from the burnt ashes of bamboo, dongon-dongong, sai-yung, salumayag, or almasiga plants.

This soot was often mixed with little water or some sort of liquid, like hog bile for the Ibanags, and the Spaniards suspected that this soot was mixed with blood. This precolonial soot mixture, which served as the tattoo ink, is called biro by the Bisayans.

As for the sharp object, it was usually a knife, lemon thorns, or other needle-like tools — a hammering stick would be an additional implement if the sharp object was not a metal blade.

TATTOO PROCEDURE

In the olden times, the tattooist would draw the sacred pattern on the recipient's skin with their soot mixture. Next, the tattooist would poke, prick, incise, or puncture the skin, following the tattoo design. Then, the tattooist would rub the fresh wounds with their soot mixture to make it more visible and permanent.

TATTOOIST PROFILE

Recent studies reveal that the profession of the preconquest tattooing was not exclusive to one gender. The Manobo tattooists were mostly females, and some were effeminate males who vowed to sexual purity, and they were traditionally paid for their services with beads, leglets, and food.

Visayan Tattoo Design And Symbol Images

It is also believed that tattooing was a lucrative profession and highly respected in the olden days. Some renowned tattoo artists would travel to different villages and tribes, for they were highly sought after for their services.

Historical narratives often compared and connected the precolonial tattooing with the traditional embroidery and weaving; hence, the tattoo artists were most likely learned weavers.

Lastly, considering the sacredness of the preconquest tattoos, it may be assumed that the tattoo artists were heavily connected with the area of ancient spirituality and practices, such as Binabaylan, Diwatahan, or Paganitohan.

REASONS FOR TATTOOS

Conventional wisdom dictates that the preconquest Philippine tattoos were only reserved for the warrior class; however, this popular statement proves to be inaccurate, for a non-warrior male, a female, and even a child, might be permitted or encouraged to have a tattoo. There were varied reasons on why to have a precolonial tattoo:

FOR IDENTIFICATION

In the olden times, tattoos were used to identify a person's tribe and address, and it could even reveal the person's name, profession, and social stratification.

FOR COMING-OF-AGE NOTICES

The Manobos started tattooing their children upon the start of their puberty. As for the Bisayans, they have a term called tigma that means a youth's first taste of sex, while tiklad is their first victory in love — and they were tattooed for these life events and for laudatory notices.

FOR THE VICTORIOUS WARRIORS

Animist champions or war leaders, such as the baganis, maganis, mangubats, or datus, were tattooed to commemorate and celebrate their feats. These warrior-type tattoos were likened to medals of honor. Thus, a man whose body was covered with warrior-type tattoos was perceived to be a very powerful and capable warrior.

Tattoos on the face, from ears to chin and around the eyes, were reserved for the greatest and fiercest Bisayan warriors who had successfully protected their villages and eliminated their enemies.

For those who had warrior-type tattoos but acted cowardly, they were ridiculed and called halo, which is a timid black and yellow bayawak or monitor lizard, by the precolonial Bisayans. And those who received warrior-type tattoos but not had defeated an enemy were scorned as phonies.

FOR DIVINE POWERS

It is widely believed that the precolonial tattoos provided special powers to their owners, giving them strength, luck, and protection from evil spirits. According to a Mindanao oral tradition, the Manobos had themselves tattooed so that the man-eating giant Ologasi, who preyed on unpainted humans, would not eat them.

FOR THE AFTERLIFE

An old Ibanag belief mentions that if their dead were unpainted, their soul could not enter their ancestral land of the dead. This belief is similar to the Kalingas, for their tattoos served as identifying marks to be recognized by their deceased ancestors who would see if they were worthy to live with them in Jugkao, their afterlife.

As for the Manobos, they have a very interesting explanation about their preconquest tattoos. According to their oral tradition, when a person dies, their world would turn into a black abyss, but if one had tattoos, their tattoos would light up and guide their soul to their resting place called Somolow.

CONCLUSION

We can appreciate the fact that tattooing was observed by the precolonial inhabitants across the Philippines, and these tattoos symbolized the rich cultures of bravery, spirituality, and identity of the preconquest Filipinos — truly, these sacred preconquest tattoo practices are cultural treasures that the modern-day Filipinos can be proud of and a tradition that must be protected and passed on.

REFERENCES

- Blair, Emma Helen, and Alexander Robertson., eds. The Philippine Islands 1493-1898. Cleveland, Ohio: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1903-1909.

- City Government of Cagayan de Oro. 'History of Cagayan de Oro.' Cagayan de Oro: City of Golden Friendship.

- Donoso, Isaac., ed. Boxer Codex: A Modern Spanish Transcription and English Translation of 16th-Century Exploration Accounts of East and Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Quezon City: Vibal Foundation, 2016.

- Jocano, Felipe Landa. Anthropology of the Filipino People II: Filipino Indigenous Ethnic Communities; Patterns, Variations, and Typologies. Quezon City: Punlad Research House, 2003.

- Pigafetta, Antonio. Magellan's Voyage Around the World, Volume I. Translated by James Alexander Robertson. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1906.

- Ragragio, Andrea Malaya M., and Myfel D. Paluga. 'An Ethnography of Pantaron Manobo Tattooing (Pangotoeb): Towards a Heuristic Schema in Understanding Manobo Indigenous Tattoos.' Southeast Asian Studies 8, no. 2 (2019): 259-294.

- Salvador-Amores, Analyn. 2017. 'Tattoos in the Cordillera.' Philippine Daily Inquirer, October 29, 2017.

- Scott, William Henry. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994.

Illustration Sources: The image detail at the top is from Planting of the First Cross by Vicente Manansala (ca. 1960s), National Museum Collections; the photo source and the image remix is brought to you by Datu Press®.

Patronage Note: If our culturally driven endeavors inspire you and give you joy, please consider becoming one of our sustaining patrons. Click here for more information. Join the Revolution! This is a public service of Datu Press®.

The world of Visayan songs has grown so much since I first listened to Baleleng. Last July 27, Cebu's music scene welcomed 10 new songs to its expanding portfolio after the finals night of the ..- See full list on datupress.com

- Pop. density. 292/km 2 (756/sq mi) Ethnic groups. The Visayas ( / vɪˈsaɪəz / vi-SY-É™z ), or the Visayan Islands ( Cebuano: Kabisay-an, locally [kabiˈsajÊ'an]; Tagalog: Kabisayaan [kabiˈsÉ jaÊ'an] ), are one of the three principal geographical divisions of the Philippines, along with Luzon and Mindanao. Located in the central part of the archipelago, it consists of several islands, primarily surrounding the Visayan Sea, although the Visayas are also considered ..

- Dec 31, 2013 · Macanduc is a popular deity to southern and southeastern Visayan tribes of yore and was believed to be a really bloodthirsty deity, who loves spreading carnage and strife in the battlefields he walks on, taking lives of people from both sides without discrimination.

- Jan 19, 2016 · The tribe has 10 epics that contain details of heroic deeds and significant events relevant to their culture. Traditionally, these epics are sung as lullabies to children at bedtime, while waiting for time to pass or during special gatherings. They were memorized by the tribe, especially by the Binukots of the community.

- The Ilianon and Langilaon were named after the border areas they occupy. The Tala-anding, named after a myth, are distinguished by the elaborate fan-like headgear their women wear during festivals. Commerce and Industy. Bukidnon has very fertile soil; the main crops are corn, rice, coffee and bananas.